My folding bike Bino hasn’t gotten much attention on this blog for a while. Simply put, he and his components are a known quantity and he is in a good state- like a comfy blanket you keep going back to.

That said, there are little things that could be improved.

One of them is something I’ve sat on for a very long time. Dahon’s stock single-leg kickstand is convenient, but it’s not very stable when Bino has loaded panniers. I’ve seen LitePro make and sell a double-leg kickstand for years, which is supposedly much more robust for the kind of bike commuting I could do on Bino. I figured it might be time to indulge.

The other “upgrade” I had in mind was the seatpost clamp. The stock Dahon unit gets a lot of use as Bino gets folded and unfolded. Perhaps it’s fair that metal fatigue has set in and it’s no longer holding the seat post as securely as it should. Even with the bolt tightened as far as it can go and the lever cammed shut, I could squeeze Bino’s saddle with my inner thighs and get saddle and seatpost to twist with less effort than you’d think. Not ideal.

I ordered both items on Lazada. Where their seatpost clamp feels quite a bit lighter than stock, the double-leg kickstand is the opposite, which is understandable considering it’s meant to be weight-bearing. For the additional utility it offers, though, I don’t really mind – I tend to be indifferent towards bike weight anyway.

First up is the seatpost clamp. I wish I could say this was an unqualified improvement over Dahon’s stock unit, but it isn’t – not quite. There are a few issues.

The main one is the little nut which the cammed quick-release lever threads into. It’s not knurled like the one on the stock Dahon seatpost clamp; instead it’s this obnoxious low-profile dome-shaped job that has six dimples in it. It’s very hard to turn or secure with fingers, and I have no idea what tool to do that with, so I basically have no choice but to treat the quick-release lever like a wingnut as I tighten it down to sufficient tension.

The other complaint I have is with the quick-release lever itself. There is a reason why you want to have sufficient tension in the “open” position: this quick-release lever likes to turn by itself. There is no mechanical means of making the lever stay in its parallel position on the seatpost clamp, other than the tension you put into its threaded rod. It feels like the cam on this lever is ball-shaped instead of cylindrical.

Once you’ve got it properly set up, it delivers much more reassuring compression on the seatpost, which is great for addressing my current problem. I’m just worried about how well it’ll hold up later on, when I may need to wind in more tension in the quick-release lever to keep the seatpost from slipping.

Cosmetically, it’s a subtle improvement. Nice weight-weenie touches abound, such as the scalloping around the circumference of the seatpost clamp itself and on the quick-release lever. That stylized “P” logo on the forward edge also serves as a good reference for centering your saddle. I just wish the quick-release lever assembly was designed a little better.

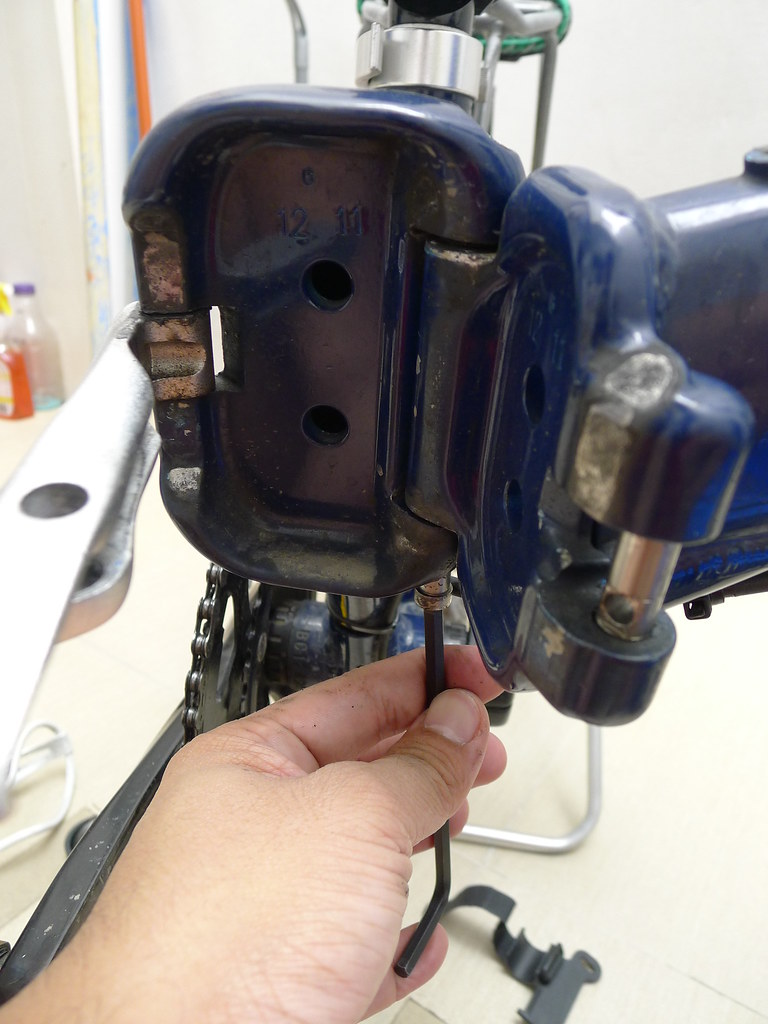

The double-leg kickstand, now that I got along so much better with.

There are silver pins on each leg, which correspond to a series of holes along each leg’s length. This tells me the kickstand is adjustable in height. Out of the box, it’s set to the correct height for a bike with 20″ (406 mm) wheels like Bino.

Additional weight aside, when installed, the double-leg kickstand is surprisingly discreet. Even its action is similar to the stock single-leg unit, the second leg opening away from the main leg by itself unassisted. The only “assist” needed is to slightly lift the rear of the bike while deploying and stowing it away, as the two legs need the space to move to their positions.

With the double-leg kickstand deployed, the weight of the unladen bike now rests on the kickstand’s two legs and the front wheel.

If you think this will allow for full drivetrain maintenance, unfortunately that isn’t the case. The crank arms will still foul the legs of the kickstand, so you’ll need to suspend the bike some other way. It’ll work great for washing the bike, though.

Overall I’m very happy with how the kickstand turned out. Sure, weight weenies will raise a stink, but from a pure utility or commuting standpoint, it is such a boon. LitePro doesn’t quote a maximum weight capacity for this, but from a build quality perspective, it just slays the stock single-leg unit with its solidity.

This has led me to wonder what else I can do to freshen up or otherwise optimize Bino. While not urgent, I may set my sights on the seatpost and handlepost next – the latter especially, because both my wife and I ride it slammed on its lowest height and don’t need the extra telescoping ability.