After inviting my wife to go riding with me one Sunday morning, I gave my folding bike Bino a quick checkup, since she was going to be riding him. Most of my riding happens with Hyro these days, so Bino is usually kept folded up in storage, and his infrequent use also means infrequent maintenance. As I learned, there is a point where too much of the latter can eventually backfire on you.

Bino’s shifting was still good, but his braking action was terrible. Pulling the levers was fine, but letting go of them revealed just how much dirt and gumming-up there was in the cables. There was none of the snappy return of the levers and calipers to their starting positions, which is annoying at best and dangerous at worst. As a temporary fix, I dripped some very thin lube – trusty old Boeshield T-9 – into the brake cable housings to get them to move smoothly again, but I knew I had to replace the cables at the soonest.

A few days after that ride, which went well, I got to the task of cable replacement on Bino. Much like Rommel’s road bike, Bino’s cables are all externally routed, but like Hyro, Bino also makes use of full-length cable housing for all four cables. The cable stops festooned all over the Dahon Vitesse frame aren’t so much real cable stops as they are supports for the cable housing, since none of them really involves terminating the cable housing and having the naked inner cable run continue.

These cable support stops also reflect Bino’s origins as a bike with no front shifting. There was none for a front shift cable, so that had to be improvised.

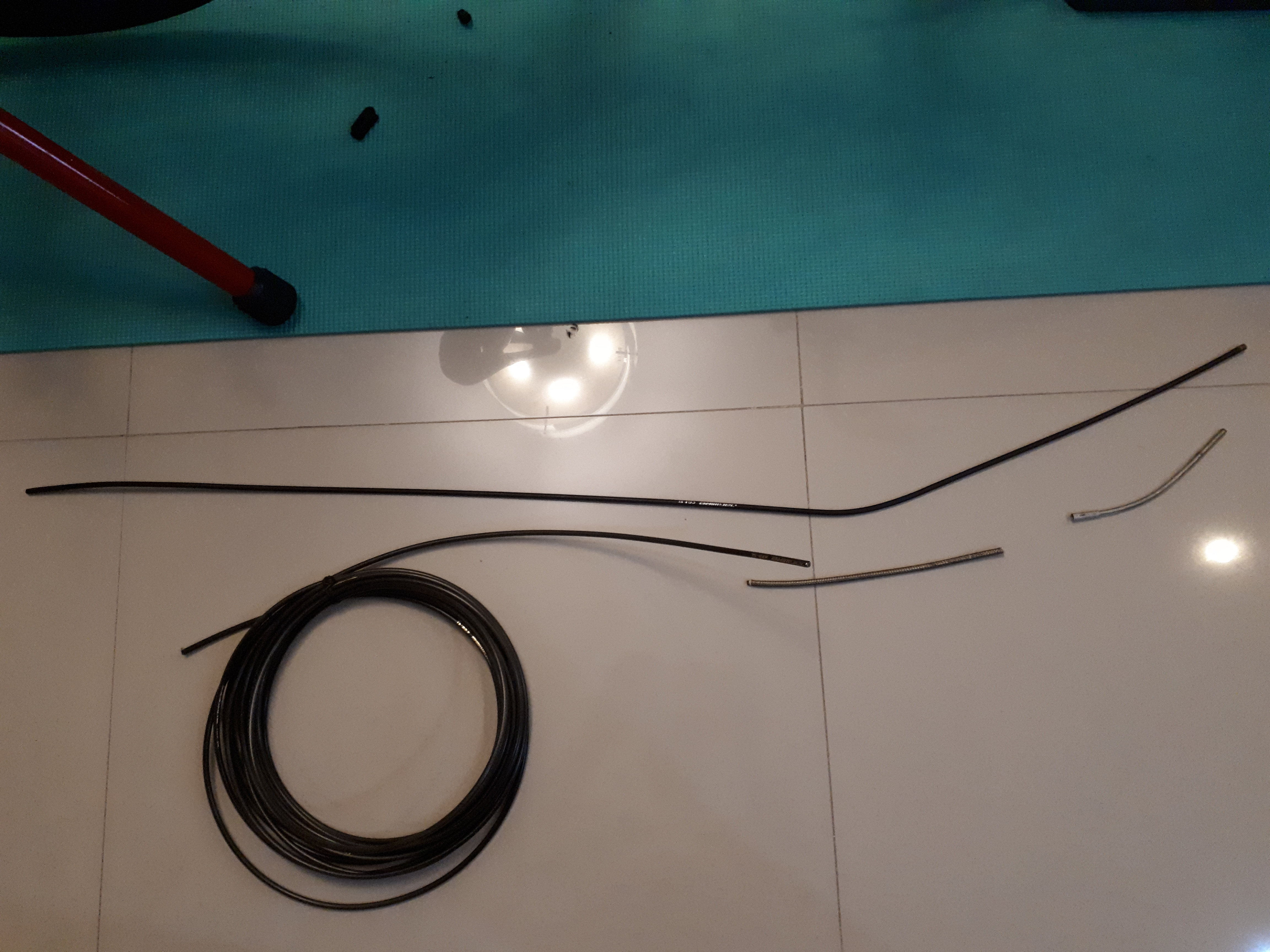

I decided to give Bino an improvement in his braking capabilities. Compressionless brake cable housing is much stiffer than normal helical-wound brake cable housing, and improves power transfer from brake lever to caliper, so I got an Alligator Sleek Glide brake cable kit. With Hyro’s hydraulic brake upgrade, Bino is now the only bike in my stable that still uses cables for braking, so I might as well give him the best. I was also curious how the stiffer compressionless housing would fit with Bino’s folding capability.

This went hand-in-hand with Shimano SP41 shift cable housing and Shimano shift inner cables. While shifting was still good, I might as well replace all Bino’s cables in one job.

To facilitate the folding capability, all Bino’s cables are suspended in a loose loop over to the non-drive side, and are bound into one with cable wrap. This allows them to curl up out of the way in a manageable bundle when the bike is folded correctly. It is important, then, to maintain this property when replacing your cables.

To release the brake cable from Shimano’s Alivio Trekking BL-T4000 levers, it’s just a matter of aligning the barrel adjusters with the open notch that goes along the forward edge of the brake levers.

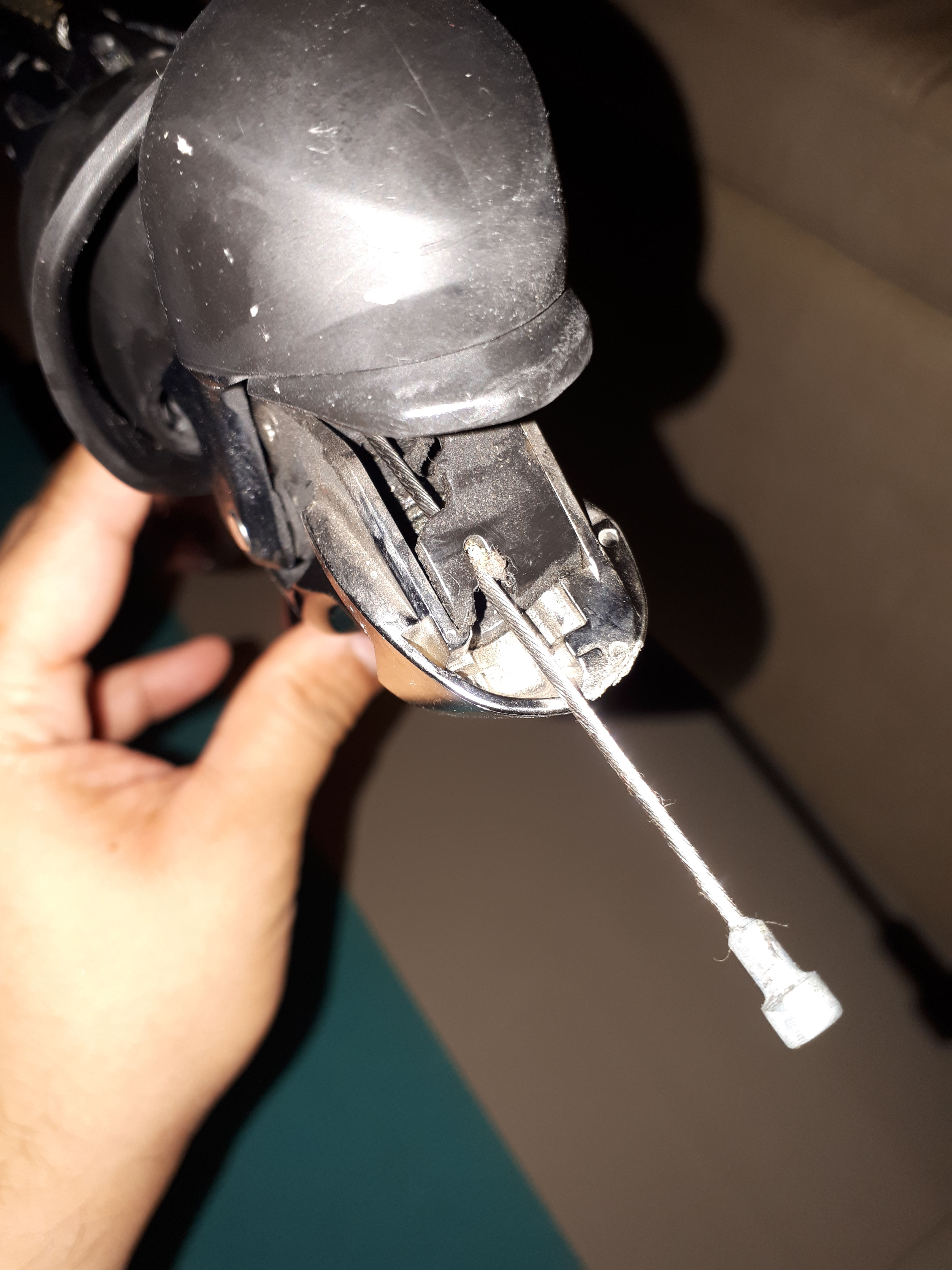

You can then pull the lever and undo the cable anchor head. The whole cable should follow.

You can see just how dirty the brake inner cable has gotten. That fine black dust is all over my fingers.

This was also a good time to shorten my front brake cable, as there was quite a bit of extra length rattling over my front fender when the Alivio Trekking V-brakes were first transferred over. Alligator’s brake housing is a little more finicky to use than Jagwire’s, with a metal inner sleeve that tends to need cleaning up with each snip of my cable cutters.

To replace shift cables on Shimano’s flat handlebar shift levers, you will need a screwdriver. After shifting down to the easiest cog or chainring and releasing all cable tension, you will need to undo a little screw that serves as a plug for the cable entry port.

Once this plastic screw is removed, it’s just a matter of pushing the old shift cable out and threading the new one in. Compared to doing the same job on my old STI levers, this was very easy to do. Just make sure you reinstall the plastic screw afterward.

Overall, replacing cables on Bino was pretty straightforward, save for having to account for the front derailleur shift cable and securing it to the bike via zip ties. The compressionless brake housings worked well and didn’t interfere with the folding, even in spite of their stiffness.